Is A Pharmacy A Specified Service Business

Executive Summary

While much of the Revenue enhancement Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 was focused on private and corporate tax reform and simplification, ane of the biggest new planning opportunities that emerged was the creation of a new 20% taxation deduction for "Qualified Business Income" (QBI) of a laissez passer-through entity, intended to provide a tax benefaction to small businesses that would leave more than profits with the business to help it abound and hire.

The caveat, however, is that the QBI deduction was but intended to provide tax benefits for profitable businesses that hire employees, not to provide revenue enhancement benefits for high-income professions who generate their profits direct from their own personal labors. As a result, the new IRC Section 199A created a so-called "Specified Service Business concern" classification that, at higher income levels, would not exist eligible for the QBI deduction.

The claiming, however, is that the exact definition of what constitutes a "Specified Service Merchandise or Business" (SSTB) has not always articulate, given the broad range of professional person services that exist in the marketplace. In addition, as presently as the rules themselves were released, artistic tax planners began to strategize almost how to adapt (or re-arrange) revenue and profits to maximize the amount of income eligible for the QBI deduction and minimize exposure to the Specified Service Business rules.

In this guest mail service, Jeffrey Levine of Pattern Wealth Alliance, and our Director of Advisor Instruction for Kitces.com, examines the latest IRS Proposed Regulations for Section 199A, which provides both important clarity to how the "Specified Service Business organisation" test will apply in various industries, including rather broadly for professions like health, constabulary, and accounting, merely only narrowly to high-profile celebrities who may have their endorsements and paid appearances treated equally specified service income merely non the income from their other businesses that may still materially do good from their high-profile reputation.

Of greater significance for many small business owners, though, are new rules that will force businesses with even just minor specified service income to treat the entire entity as an SSTB, limit the power of specified service businesses to "cleave off" their non-SSTB income into a separate entity, and in many cases aggregate together multiple commonly owned SSTB and non-SSTB business organisation for taxation purposes.

Ultimately, the new rules are just impactful for the subset of small business concern owners who engage in specified service business organisation activities and have enough taxable income to exceed the thresholds where the phaseout of the QBI deduction begins (which is $157,500 for individuals and $315,000 for married couples). Notwithstanding, for that subset of loftier-income business organisation owners, constructive planning to avoid having SSTBs "taint" not-SSTB income, or to split off non-SSTB income to the extent possible, will be more challenging than earlier.

IRS Issues Proposed Regulations one.199A On The Qualified Business Income Deduction

On August 8, 2018, the IRS released the much-anticipated proposed regulations for IRC Section 199A. The regulations provide a veritable treasure-trove of information, and in particular, articulate upwardly many of the questions surrounding Specified Service Trade or Businesses (SSTB). Most importantly, they provide much-needed clarity to make up one's mind exactly what businesses should exist classified as an SSTB (or not). This determination is of minimal importance to low and moderate income earners (up to $315,000 for married couples filing joint returns, and upward to $157,500 for all other filers), only is disquisitional to high earners above those thresholds, who may come across their qualified business income (QBI) deductions related to specified service trade or businesses partially or fully phased out as their income exceeds those thresholds.

Understanding The Definition Of A Specified Service Trade Or Business (SSTB)

The principal purpose of the IRC Section 199A deduction for Qualified Business concern Income (QBI) was to provide a tax boon for businesses that rent and use people to grow the US economy, only non to give a deduction to those who simply earned a substantial income from the fruits of their own labor. Not that all service businesses would be prohibited… just specifically the ones that generated income primarily past providing various types of professional services.

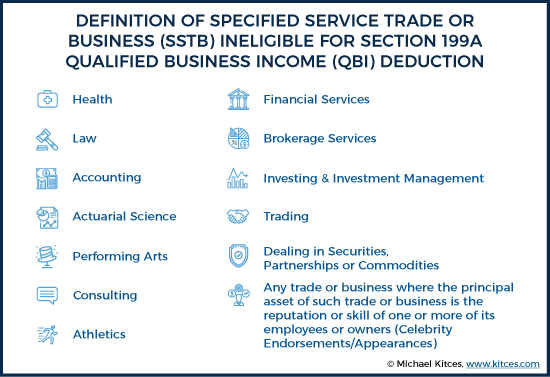

Appropriately, IRC Section 199A defines certain "SpecifiedService Trade or Businesses" (SSTBs) that, at higher income levels, are not eligible for the QBI deduction. Drawing on IRC Section 1202(e)(3)(A) (which defines eligibility for certain types of modest business stock capital gains to be excluded from income, and similarly is not available for professional services firms), the legislative text of IRC Section 199A stipulated that an SSTB would include:

"…any trade or concern involving the performance of services in the fields of wellness, police, accounting, actuarial science, performing arts, consulting, athletics, financial services, brokerage services, or whatever merchandise or business where the main asset of such merchandise or business is the reputation or skill of ane or more than of its employees."

(Notably, IRC Section 1202(e)(3)(A) also includes engineers and architects, simply those professions were explicitly excluded from the list of SSTB professions under IRC Section 199A(d)(2)(A).)

In addition to the businesses listed above, IRC Section 199A(d)(2)(B) adds the following businesses to the listing of SSTBs:

"…whatever trade or business which involves the performance of services that consist of investing and investment management, trading, or dealing in securities."

While some of these professions are relatively straightforward to define, the original legislative text for Section 199A left much up to interpretation when determining whether or not certain businesses would be treated as a specified service merchandise or business (SSTB), both with respect to certain border cases within professions (east.yard., does an auditor who but does tax preparation only not business accounting and auditing all the same "count" equally accounting services, and does income from selling insurance products count as "financial services" or only providing investment advice?), and the relatively broad catch-all at the end of the SSTB list for "any merchandise or business concern where the principal asset of such merchandise or business is the reputation or skill of 1 or more of its employees" (raising the question of whether a eating house qualifies for the QBI deduction, but a eating place with a star chef might not?).

Clarifying The Scope Of Professions That Are "Specified" Service Businesses

Fortunately, the new IRC Department 199A regulations provide a groovy deal of clarity about where, exactly, to draw the line between the 13 different types of specified service businesses and all other types of service businesses.

Some types of SSTBs are relatively straightforward and required minimal clarification from the IRS, such as athletics and performing arts. The regulations do, however, analyze that persons engaged in supporting services, such as those who maintain or operate equipment or facilities for such businesses, are not SSTBs, themselves.

Determining what types of and roles within various professional service occupations fall into – and just as important, exercise non autumn into – the other SSTB categories was less clear from the original legislation, though, and thus required more specific guidance from the IRS in the regulations.

Health, Constabulary, and Accounting Services Are Defined Broadly For Specified Service Trade Or Business concern

Given that the healthcare sector is now the largest employer in the US economic system, "Wellness" services was 1 area where there were a number of open up questions about the scope of the specified service rules. For instance, while it's relatively straightforward that doctors are in the health profession… it was less articulate whether pharmacists and like 'related' healthcare professionals would be included in the definition, too as veterinarians and others providing "healthcare" to non-humans. The proposed regulations take an inclusive approach hither and brand articulate that both pharmacists and veterinarians are considered health services, and thus, are SSTBs. Appropriately, the newly proposed regulations stipulate that:

"…the performance of services in the field of health means the provision of medical services by individuals such equally physicians, pharmacists, nurses, dentists, veterinarians, concrete therapists, psychologists and other similar healthcare professionals performing services in their chapters as such who provide medical services directly to a patient (service recipient)."

The proposed regulations likewise take a similarly inclusive arroyo with respect to the fields of "bookkeeping" and "law." Equally a outcome, the sometime includes not simply "accountants," but as well "enrolled agents, return preparers, financial auditors, and like professionals," while the latter also includes "paralegals, legal arbitrators, mediators, and similar professionals" in addition to lawyers, themselves.

Not All Fiscal Services Are Treated As SSTB Financial Services

Of particular importance to fiscal professionals, five of the 13categories of SSTBs directly relate to diverse professions inside the financial industry (financial services, brokerage services, investing and investment management, trading and dealing in securities, partnerships or commodities), while two more could relate indirectly (consulting and the "principal asset is the skill or reputation of one or more employees"). Thus, many high-income owners of financial services businesses will be considered owners of an SSTB and will begin to encounter their QBI deduction phase out once their income exceeds their applicable threshold.

Some of the financial services professions explicitly "called out" in the proposed regulations equally unequivocally being SSTBs include "financial advisors, investment bankers, wealth planners, and retirement advisors," as well as those "receiving fees for investing, nugget management, or investment management services, including providing advice with respect to buying and selling investments." Businesses engaged in either the trading or dealing of securities, commodities, or partnership interests are also SSTBs, equally are brokers of securities (i.due east., registered representatives of a broker-dealer).

While most financial services professionals are engaged in SSTBs, the regulations do exclude real estate agents and brokers from the definition of an SSTB as well. More chiefly, though, the regulations also grant 2 other very notable exceptions to the rule: traditional bankers (not investment bankers), and insurance agents or brokers. Is this simply because they have meliorate lobbyists than the remainder of the fiscal industry? Perchance that played at to the lowest degree some role, just the crux of the issue tin can be traced dorsum to the initial legislative text creating the QBI deduction.

Equally noted before, under IRC Section 199A(d)(2)(A), an SSTB is whatever business described in IRC Section 1202(east)(3)(A), other than engineers and architects (who apparently besides have very good lobbyists!), including:

"…any trade or business involving the functioning of services in the fields of health, police force, accounting, actuarial science, performing arts, consulting, athletics, financial services, brokerage services, or whatsoever trade or business where the principal nugget of such trade or business is the reputation or skill of 1 or more of its employees."

Conspicuously absent-minded from the list of businesses higher up are banking and insurance. Notably, these businesses are included in the following subparagraph of the IRC, IRC Section 1202(e)(iii)(B), which states:

"any banking, insurance, financing, leasing, investing, or similar business organisation"

Nonetheless, when Congress wrote the police force defining what constitutes an SSTB, information technology explicitly stated only the professions under IRC Section 1202(e)(three)(A) – and not IRC Section 1202(e)(3)(B) – would count. Accordingly, the IRS determined in its proposed regulations that a more than narrow estimation of "fiscal services" (one that does not include traditional banking or insurance services) was advisable. Subsequently all, if Congress wanted to include those businesses in the definition of SSTBs, they could have referenced both IRC Section 1202(east)(3)(A) and IRC Section 1202(e)(3)(B) when it created IRC Section 199A. Its failure to do so provided the IRS with enough legislative intent that they explicitly excluded those businesses from the definition of an SSTB in the regulations.

As a result of the deviation between the way qualified business income from financial planning/securities brokerage/investment communication is treated as compared to qualified business income from insurance services, many registered investment advisors and/or securities brokers who likewise bear insurance business will find that the profits from their different businesses will be treated markedly different from one another. While profits from the financial planning/securities brokerage/investment advice business(es) will be potentially ineligible for the QBI deduction once the owner'south taxable income exceeds $207,500, or $415,000 if married and filing a joint return, profits from the insurance business may notwithstanding eligible for the deduction as a not-SSTB (though calculating the deduction would still involve analyzing the W-two wages paid by the insurance business, likewise equally any depreciable property owned by the business, nether the separate wage-and-property test for the QBI deduction).

Unfortunately, though, it is non uncommon for certain advisors, especially solo-advisors, to run both their brokerage/informational revenue and their insurance acquirement through the same "fiscal advisor" sole-proprietorship. In the by, this often fabricated sense, equally treating the brokerage/informational business as a separate business from the insurance-related business concern would generally lead to unnecessary complexity and expense, both from the requirement to proceed two sets of books, too equally the need to file multiple Grade Schedule Cs (or other business organization returns) with the advisor'due south personal income revenue enhancement return.

Now, even so, in light of the proposed regulations' differentiation between the profits of the ii businesses, loftier-income advisors may wish to more clearly separate and delineate these different "lines of business" into two, distinct businesses. If not, the proposed regulations' de minimis rule, discussed in greater depth below, could "taint" any insurance services profits that would otherwise be eligible for the QBI deduction.

When the legislative text for IRC Department 199A was created, ane of the almost nebulous aspects of the definition of an SSTB was the take hold of-all provision that, "whatever trade or business where the principal asset of such trade or business organization is the reputation or skill of 1 or more than of its employees," is an SSTB. How would the IRS make up one's mind whether an employee or business owner'south "skill or reputation" was the driving forcefulness behind the business's profits? Rightfully so, many practitioners were concerned that this language could ensnare just about whatsoever concern with a successful and high-profile founder/owner.

For case, "Jan'south Piece of furniture Shop" probably doesn't fall into the category of an SSTB. Just what if Jan was highly regarded as the most skilled article of furniture maker in town, and her reputation as a skilled craftsman was what collection sales? Exactly how skilled or respected would Jan accept to be before the business crossed over from a non-SSTB to an SSTB? Similarly, "Bob'southward Diner" probably isn't an SSTB, but what if "Bob" was actually famous chef Bobby Flay? Clearly, such an assay is highly subjective at best, which was a primary driver of many practitioners' concerns.

Thankfully, these concerns are no longer necessary. In what was a relatively surprising motion, the IRS defined the meaning of a merchandise or concern where the master asset of that business concern is the reputation or skill of one or more employees or owners in, mayhap, the narrowest of possible means.

According to the proposed regulations, a business is just considered an SSTB by virtue of the "reputation or skill" provision if, and merely if, it generates fees, compensation, or other income via one or more of the following:

- Endorsements of products or services;

- Apply of an private'south image, likeness, proper name, signature, vocalization, trademark, or whatsoever other symbol associated with the private's identity;

- Appearances on radio, boob tube, or other media.

Equally a result of the IRS's extremely narrow estimation of the "reputation or skill" provision in the 199A regulations, the provision has gone from potentially being one of the primary culprits of classifying a business concern as an SSTB, to being fairly benign, and applicable merely to an extremely limited number of "businesses" that are truly built around "celebrity" endorsements, appearances, and the like.

In fact, the proposed regulations include a number of IRS-provided examples, and Example viii of Section 199A-five(b)(3) of the regulations provide maybe the all-time insight as to how narrowly the IRS has framed this "reputation or skill" provision.

H is a well-known chef and the sole owner of multiple restaurants, each of which is owned in a disregarded entity. Due to H'southward skill and reputation as a chef, H receives an endorsement fee of $500,000 for the use of H's proper noun on a line of cooking utensils and cookware. H is in the trade or business organisation of being a chef, and owning restaurants and such trade or business is not an SSTB. However, H is also in the trade or business of receiving endorsement income. H'due south trade or business consisting of the receipt of the endorsement fee for H's skill and/or reputation is an SSTB within the meaning of paragraphs (b)(1)(xiii) and (b)(2)(14) of this department.

If the chef in the case above is able to receive an endorsement fee of $500,000 for the use of their name on a line of cooking utensils and cookware, it's probably pretty safety to assume that they are not only a pretty expert chef (i.e., they are skilled) but that they are too fairly well known (i.e., has a potent reputation). As such, two of the primary drivers of the chef's restaurants revenues are probable the chef's skill and reputation. And yet, in the example, the IRS makes articulate that these restaurants would not be considered SSTBs, as they do non meet the (favorably) rigid definition of the "reputation or skill" provision outlined in a higher place, despite the fact that they are likely successful at least in textile role to the "reputation or skill" of their celebrity chef-owner.

Many businesses appoint in more than one specific activity or business concern line at a fourth dimension, creating a potential challenge to decide whether or non the business organization, as a whole, is an SSTB. In some cases, this is ostensibly easier considering the business lines are literally separated into discreet separate entities, for liability protection and/or other purposes (fifty-fifty though they're still "related" entities). Though in the extreme, separating businesses into detached entities also creates the concerning potential (at least for the IRS) that firms volition carve off what otherwise would take been SSTB profits (not eligible for the QBI deduction) into separate entities that would qualify (even though in the aggregate it shouldn't have).

Accordingly, the proposed regulations provide guidance on how to bargain with both circumstances, both with respect to determining when the SSTB revenue in an otherwise not-SSTB business must be treated as such, and when and whether to aggregate back together separate-but-related SSTB and non-SSTB entities into one SSTB.

Application of the "De Minimis Rule" In Determining A Specified Service Trade or Business

Often, a single business organisation will simultaneously carry multiple concern activities. In some situations, one or more than of those discrete activities, if conducted past a separate concern, would crusade that business to exist treated as an SSTB. The proposed regulations practice not, as some had hoped, allow a unmarried business to separately account for different lines of revenue and expenses and segregate SSTB profits vs. non-SSTB profits. Instead, the entire business is either an SSTB… or it'south not. As such, either all of the profits of a business are profits of an SSTB entity, or all of the profits are profits of a non-SSTB.

This raises an obvious question… how much revenue can a single business generate from an activity that would be considered an SSTB if conducted in its own, carve up business, before the entire business is considered an SSTB? The answer, unfortunately, is "not much."

Nether the proposed regulations, if a business has gross revenue of $25 million or less during a taxable twelvemonth, then the business must keep its SSTB-related revenues to less than ten% of its gross revenue to avert SSTB status. Or conversely, the $25M-or-less-revenue business will be considered an SSTB if just x% or more of its gross revenue is derived from an SSTB-type activity!

In the event a business generates more than $25 million of revenue during a taxable twelvemonth, the SSTB rules are even more restrictive. Such businesses will be considered an SSTB if just 5% or more of their gross revenue is derived from an SSTB-related activity.

Example #1: Frank is an optometrist, and is the sole possessor of Spectacular Spectacles, LLC, which is primarily engaged in the manufacturing and auction of eyeglasses (non an SSTB-related action). Occasionally, however, Frank will perform (and charge for) middle examinations, in part, to decide a client'due south correct prescription. These exams are related to health services, and thus, are an SSTB-related activity.

In 2018, Spectacular Glasses, LLC generates $three 1000000 of gross revenue. The $3 million of gross revenue is comprised of $2,880,000 one thousand thousand of revenue related to the manufacturing and sales of eyeglasses, with the remaining $120,000 of revenue attributable to Frank's occasional vision exams. Since merely 4% ($120,000 / $3 million = 4%) of Spectacular Spectacles, LLC's total acquirement is comprised of SSTB-related acquirement, the business will not be considered an SSTB.

Specified Service Revenue Taints Non-SSTBs And The Incidental SSTB Dominion

There are a number of interesting corollaries to the SSTB de minimis rule. Most notable is the fact that although it's business'southward profits that are eligible for the QBI deduction in the first place, the determination of whether or not a business with acquirement from multiple activities is considered an SSTB is determined solely by the ratio of its acquirement from SSTB activities in relation to its total revenue. Which is concerning, considering it ways a loftier-revenue depression-margin specified service business can taint the QBI deduction for an unabridged high-turn a profit non-SSTB!

Example #ii: Bill, one of Spectacular Glasses, LLC's employees, decides to get out and start his ain eyeglass manufacturing and sales company, Glasses for the Masses, LLC. Bill is not a doctor, only in an effort to drive business organization and compete with his former employer, he hires several optometrists who can perform vision examinations and heavily promotes and advertises this service.

In 2018, Glasses for the Masses, LLC generates $one.6 million of revenue and $550,000 of profits. As a result of the profits, Neb is over his applicative threshold, and thus, will be ineligible for any QBI deduction if his business organisation is deemed an SSTB.

Analyzing Glasses for the Masses, LLC's acquirement and profits farther, it is adamant that $400,000 of the company'due south total revenue is derived from the heavily marketed eye examinations. Yet, after accounting for expenses, including the salaries of the two optometrists, this action merely generates $50,000 of turn a profit. In dissimilarity, the cadre business of manufacturing and selling eyeglasses generates $1.2 million of revenue, and $500,000 of profit.

Simply nearly 9% ($l,000 /$550,000 = 9.09%) of Glasses for the Masses, LLCs profits are attributable to an SSTB-related activity. The entire business, yet, and all of the profits, volition be considered an SSTB for 2018 since 25% ($400,000 / $1.six million = 25%) of its revenues are owing to the SSTB-related optometry activity… well more than than the x%-of-revenue hurdle necessary to current of air upward with that categorization. The end result? Bill gets $0 of QBI deduction on his $550,000 of profit (about all of which was not-SSTB profit, merely all of which was butterfingers every bit a high-income SSTB business organisation even so!).

For business owners like Bill, there are a couple of dissimilar options.

One option, for instance, would be to simply eliminate the SSTB-related activity that's not all that profitable in the first identify. Unfortunately, that may be easier said than washed. What if much of Glasses for the Masses, LLC's revenue and profits from the manufacturing and sale of spectacles (not-SSTB-related) is due to the fact that customers are able to get an eye examination and purchase their eyeglasses in one location (which, in the extreme, could make it worthwhile to proceed the SSTB service that disqualifies the QBI deduction simply considering it'southward "necessary" for the business)?

Another selection for business organization owners like Nib is to split the various activities into legitimate, bona fide, carve up businesses. In such situations, each business will generally be evaluated on its own claim. Splitting activities into dissever businesses in this manner (e.g. creating GM Optometry to perform optometry services) might create some operational challenges for Neb, such as the demand for customers getting an middle test and purchasing glasses to pay two separate bills to the two dissever companies (an eye exam nib to the optometry business and a glasses bill to Spectacles for the Masses, LLC), simply the resulting tax benefits may be worth it. In Bill'southward case, it would mean a 20% tax deduction on up to $500,000 of profits… annually!

On the other hand, the proposed regulations exercise have an additional layer of rules specifically intended to limit splitting off a multitude of pocket-sized not-SSTBs to insulate them from an SSTB core (which wouldn't be applicable in the example higher up, merely could be an issue for an optometrist that primarily provided eye exams as health services and only sold a few eyeglasses "on the side"). Specifically, under the "incidental-to-SSTB" rules, if a non-SSTB has 50%-or-more common ownership with an SSTB and has shared expenses, it must have revenues of more than 5% of the combined revenues of both businesses, or they volition all be aggregated equally an SSTB anyway. Accordingly, in order to exist treated as a separate SSTB (and not taint the not-SSTB core), the separate business must either take revenues of more than 5% of the combined entities, or accept its own entirely independent cost structure and not share wages, overhead, or other business expenses.

Instance #iii: Jerry, Spectacular Glasses, LLC's nearly popular optometrist, decides to go out on his own as an optometrist, and over iii years quickly grows to generate $500,000/yr of acquirement. While Jerry's business is solely focused on providing optometry (health services), which is an SSTB, his wife Elaine (an artist) suggests that he start selling a pocket-size number of designer eyeglasses (with her art designs).

Later two more than years, Jerry's optometry practise grows to $600,000/yr in acquirement, and his wife's separate eyeglass business (sold in Jerry'southward medical offices) generates $xv,000 of revenue. Normally, an eyeglasses business is not an SSTB, but because Elaine'south eyeglass business organization is under common ownership with Jerry's optometry business (via the shared attribution rules for married couples), and they share expenses (since she uses Jerry's office space to sell her glasses), and the eyeglass acquirement is simply 2.4% of the combined $15,000 + $600,000 = $615,000 revenue, any profits on Elaine's eyeglass business volition be treated as SSTB income (phasing out their QBI deduction altogether given Jerry's high income).

Farther complicating the thing is the fact that a business organisation conducting both SSTB-related and non-SSTB-related activities may periodically change from an SSTB to a non-SSTB (or vice versa), and dorsum once again, depending upon the ratio of SSTB-related acquirement to total revenue each twelvemonth.

This is possible because, nether the proposed regulations, the de minimis dominion states that:

"For a merchandise or business organisation with gross receipts of $25 1000000 dollars or less for the taxable twelvemonth , a trade or business is not an SSTB if less than 10 percent of the gross receipts of the trade or business organisation are attributable to [an SSTB]". (emphasis added)

The key point is that the proposed regulations' stipulate that the de minimis rule is practical separately "each taxable year." As a result, the conclusion of whether a business conducting both SSTB-related and non-SSTB-related activities is itself an SSTB is an annual test, based on whether the SSTB-related acquirement is more than 10% (or in the case of >$25M revenue businesses, more 5%) in each year!

The lxxx/50 "Spin-off Killer" Rule (A.K.A. The Anti- "Cleft and Pack")

About immediately after the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act'south creation of IRC Section 199A, practitioners went to piece of work dissecting the new section and coming upwardly with creative means to allow clients to claim greater deductions.

1 of the most widely discussed strategies for high-income business concern owners was something that came to be known as the "cleft and pack." In brusque, the "crevice and pack" was just the thought of spinning off certain elements of an SSTB – often business-endemic existent estate - into a separate, ordinarily-owned entity, in order to shift income from an SSTB (for which a QBI deduction on profits may have been phased out) to a not-SSTB (for which a QBI deduction on profits may all the same be available).

Unfortunately, the proposed regulations put a astringent wrinkle – if not a death knell – in the "crack and pack," thank you to the new "80/50 dominion" outlined in Department 199A-5(c)(ii) of the regulations.

Under this provision, if a "non-SSTB" has l% or more mutual ownership with an SSTB, and the "non-SSTB" provides lxxx% or more of its belongings or services to the SSTB, the "non-SSTB" will, by regulation, be treated as part of the SSTB.

Example #4: Betty is a doctor, and is the sole owner of her do, which is organized equally an LLC. The net income from her practice – which falls under the "health" services category of the SSTB definition – is $800,000 per twelvemonth. Every bit a result, Betty cannot claim a QBI deduction. Betty's LLC also owns the medical office out of which she practices, having purchased it several years agone for $2,000,000.

Prior to the issuance of the proposed regulations, one strategy Betty might have contemplated with her tax planner was spinning the medical part out into a separate LLC, or other concern structure, and having the medical practice pay rent to the rental business for its use of the property. Prevailing wisdom was that while the profits of the medical practice would have been ineligible for the QBI deduction, the profits from at to the lowest degree the new (at present-dissever) rental business organisation would have eligible for at least a partial QBI deduction (effectively converting that portion of the income from SSTB to non-SSTB income).

The proposed regulations brand articulate that such a serial of transactions would now be fruitless. Bold that Betty's medical practise connected to use 100% of the office space after it was spun out into a new entity, she would be in "violation" of the "80" role of the fourscore/50 rule, since more than than 80% of the not-SSTB's property would be used past a SSTB. Similarly, assuming she was the possessor of the business organization into which the medical part was transferred, she would be in violation of the "l" part of the 80/50 dominion, since the common ownership between the SSTB and the non-SSTB would be 100%! Thus, the rental business organization and its income would, by rule, still be treated every bit an SSTB.

The "best" way to "beat" the 80/fifty rule volition often be to "attack" the "l" part of the rule by trying to get the mutual buying between the SSTB and the not-SSTB business organisation entities below l%. In one case the common buying (which includes both direct and indirect buying by related parties) between the two entities is less than 50%, the anti-"crack and pack" rules don't apply, and the non-SSTB volition actually exist treated as a non-SSTB!

Notably, trying to avoid the 80/50 dominion by but ensuring the SSTB business uses less than 80% of the non-SSTB's holding and services (e.g., by buying the entire medical role circuitous, renting out the other suites, and using just a small portion of the office infinite for the normally endemic medical practice) volition but exist of limited effectiveness. The reason is that, under the rules, if a "non-SSTB" is providing less than eighty% of its services/property to a fifty%-or-greater commonly-owned SSTB, a portion of the business's profits will still be considered part of an SSTB! In such situations, the portion of the business organization's services/property that is non provided to the commonly-endemic SSTB will not be treated as an SSTB, but the portion of business concern'due south services/property that is provided past usually-owned SSTB will however be treated every bit an SSTB!

Example #five: Kanwe Beatum, LLC, is a police house, and thus, an SSTB. The owners of the business firm have recently decided to buy a large office building in a dissever (but commonly owned) entity, Fancy Offices, LLC, of which 40% volition be rented to Kanwe Beatum at fair market place value to behave time to come operations, while the other 60% will be rented to unrelated businesses.

Hither, only 40% of the non-SSTB Fancy Offices holding (the building) volition be provided to the SSTB law firm (which is lower than the 80% threshold). The ownership, even so, between Kanwe Beatum, LLC and the Fancy Offices entity in which the office building is purchased is identical (≥50%). As a event, 40% of Fancy Offices will be treated as an SSTB (i.eastward., twoscore% of its revenue and profits will exist subject to the SSTB phaseout tests), while the remaining 60% will non.

Ultimately, the "good" news of the new SSTB rules is that they nonetheless merely apply to a limited subset of small business owners – those that do engage in at least some level of "specified services", and have income that is high enough to exceed the thresholds ($157,500 for individuals and $315,000 for married couples) where the QBI phaseout kicks in. Nonetheless, for high-income small business owners who do meet those thresholds and have specified service income, careful planning will be more important than e'er to avert running afoul of the new rules, especially with respect to trying to separate (and avoid "tainting") non-SSTB income from the less-tax-favored income of specified service businesses.

Source: https://www.kitces.com/blog/sstb-specified-service-business-de-minimis-rule-crack-and-pack-80-50-rule-qbi-deduction/

Posted by: smiththeyes.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Is A Pharmacy A Specified Service Business"

Post a Comment